I’ve been trying to write about being here for the better half of a year—so much so that I began to doubt that I ever would—and now it’s seven in the morning, I’m sitting in a corner cafe a few streets away from my apartment, and I feel bereft. It’s been exactly a year since I arrived, and I so deeply want to go home. I often find myself wishing that I could just turn the corner and be home, real home, not where I live now with all the trinkets I’ve asked visiting friends to bring over. I cannot help but think of Borges: What use now are my talismans, my touchstones / it is love. I will have to hide or flee.

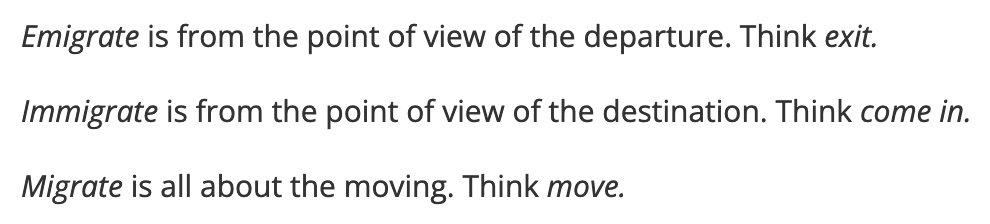

I’ve looked up the definition of immigration to see if it applied:

The definition of immigration includes permanence. So maybe I’m not an immigrant quite yet. The inclusion of ‘yet’ is troubling. I never thought I’d want to stay. To live here, for me, is to have those parts of myself warring at all times: stay, or go home. In those few, quiet moments in bed, between the sirens and scattered conversations I hear from my window, I think about what to do next.

When I was packing for New York, it was as if my dogs could tell that I was preparing to leave. Gaby, my Belgian Malinois mutt, ran out of the house and attacked a stray cat my neighbors have all but adopted—or she tried to, at least. The cat bit her leg and Gaby finally came limping back, and I had to drive around to three clinics before finally finding a vet that could check for rabies and clean up the wound. We laughed at how this big dog could be taken down by a stray. When I left the house on the day of my flight, Gaby was trembling as I hugged her. I’m sure she could sense all my big feelings, mistaking my tears for anger.

Gizmo, my tiny gremlin of a Yorkshire Terrier, developed a limp a few days after Gaby’s attack. I spent a significant amount of money to get an X-Ray only to find that his age was catching up, and he was prescribed joint supplements. After a day with me to the vet, he was fine, back on all fours, yapping away. Before my flight, I had to coax him over for my last pets and kisses. Even now, I tell myself that he knew, he must have—and it’s as if he wanted to stretch out the time between us as much as he could, knowing that I wouldn’t leave until I gave him a final kiss on the top of his head.

I leave for a three-week trip South Africa in two days and I’m convinced that leaving Manila has zapped me of any desire to travel. That, and my student visa status just makes me nervous, irrationally so: I have an unfounded fear that for some reason or another they won’t let me back in, and all my stuff will just be moved to some unnamed storage facility that will end up in a reality TV show for people to bid on. Not that I have anything of external value, but those bidders don’t know that.

Every new person I meet here gets a similar spiel: I didn’t even want to come here. The United States of America was the last place on my mind when I was looking for schools to apply to. And now here I am. At any point in the day, there are two things running in the back of my mind—a running balance of my checking account and potential areas of employment once my program ends in December. The immigrants I’ve talked to shared the same sentiment: your visa status will loom over your head forever, up until you get a green card or some other form of acceptance, approval, admittance to this country of immigrants. Otherwise, every piece of First Class Priority Certified Mail will strike some terror into you.

I quite arrogantly assumed that I would be immune to all this, that my desire for home would overcome any and all pressure to remain. I imagined that my time here would be fixed—a year and a half, then I’m done, I’m back home, eating meals my dad cooked off of my mom’s carefully curated porcelain collection, my dogs laying by my feet, with plans to see friends for coffee, dinner, or drinks. Instead I’m here, calculating the optimal time for calls back home with the time difference between Pretoria and Manila.

Maybe I’m too old for this. I’ve seriously considered that as a possibility to explain this malaise. Maybe it’s time to put away my passport and just go home, to all my creature comforts and familiar routines. I’ve quit for less.

I’ve been on the other side of this often enough. My proposal for my term paper in Applied Econometrics class began like this: “Every Filipino knows someone who has left the country to live and work elsewhere; it has become a fact of life.” I first experienced this when I was in my early teens and my cousin emigrated to Australia. I remember how all of us, a whole barangay1 of Ramoses, piled into as many cars as we could and brought her to NAIA and ate Jollibee as her last meal in Manila. Then again came the mass departures of my friends in 2016—three friends in the span of two months, all to the East Coast. A few years later, three friends were off to Australia and Italy. There is no getting used to saying goodbye, there’s no getting used to being left behind (and there must be a better way to say it, but then again, what else does it feel like?). Still, even then, I felt the split between myself: happy for you, sad for me. I felt both the selfish desire of wanting them to come back to me alongside the desire to see them succeed in their wishes to be away.

Every friend who’s come to visit has told me that I fit here, in this city. After a year, I find that I’m beginning to agree with them. That shouldn’t scare me as much as it does, but my knee-jerk reaction is to continue to reject it: I’m only here for two years and some change, and that’s as far as I have planned. God forbid I begin to grow roots here.

I’m ashamed to admit that, still. That I want to be here for two years, or more, whatever, whatever. At first, it was just until the end of my program. Now I want a bit more time—at least a year more, at least, and the “at least” is the sticking point. I wonder when I will stop wanting more of it. I fear that I won’t.

Economics is derived from Ancient Greek οἰκονομία (oikonomia) which is a term for the “way to run a household.” This is the first time in my life that I’ve been fully independent—and for me, that meant having to figure out what to eat all the time. I get it now, I get my mom’s desire to just order meal plans over groceries during the pandemic, because there is a certain mental load to thinking of what ingredients to buy from the grocery to make a meal that isn’t depressing. Which is all to say: I have not cooked this much Filipino food in my life. I also started seeing a therapist here, and with her came to realize that maybe the reason I enjoy cooking here is because it’s my own kitchen and not my grandmother’s. In Manila, cooking was a labor of love, in the most literal sense. Here, I’ve found freedom in making mistakes and trusting my gut; there’s no pressure on enjoyment beyond my own.

Over the year that I’ve been here, I’ve tweaked the balance sheet in my brain and allowed myself some minor life improvements. One of the first things I bought was a renter-friendly hook to put up by my bedroom door, because I fear losing my keys and locking myself out. A new friend, G, described my purchases and constant fixing-up as “nesting,” and I find that it’s true: a new duvet and its covers, prints to go up on the wall, a spinning tray for my skincare. When D was here to visit, we picked up an end table from the sidewalk and now I have somewhere to mount my mirror. I’ve also bought my own chef knife and sharpener, as well as a well-reviewed baking tray because I’ve become obsessed with roasting vegetables.

Living here now has also put my preferences into high relief. I only packed two books from Manila (The Artist’s Way of course, and a 1970s copy of the Audubon Society’s Guide to North American Birds from C) and somehow I have accumulated five more (granted, they’re all nonfiction and related to international political economy), along with two books from home that I asked friends to buy for me (

’s Nail Down the Sky, and But for the Lovers). Now I have a shelf full of books and another shelf for my stationery and fountain pen inks. My precious cargo.What’s new and never existed in my room in Manila are my plants. It all started when my housemate brought out a dying pothos from her room and some animal part of me thought, I need to save her. It was at the tail-end of fall, and I worried about the cuttings throughout the winter. Somehow, now, I have four pots of thriving plants and I love them dearly.

Through Anne Carson’s Eros the Bittersweet, I learned the Greek definition of the word: Pothos (πόθος) is a Greek for longing, yearning, desire, regret. It was close to midnight as I read the book, and I could not help but laugh to myself at the perfect metaphor. The plants that I heralded for our shared survival of our first New York winter, whose name describes the tangle of emotions that stir in me when I think of home (which is always) and how home now means both Manila and the shoe box with a north-facing balcony that’s a 15 minute walk from the subway station.

I’ve never really considered what it felt like to be the one leaving, and how living in another country does, in fact, cleave one in half. A selfish part of me wishes that weren’t true, that I could just take this experience and be the same as I was before, and that the same would apply for everyone at home. All this meandering has been a way of putting off admitting that I have selfishly desired that everything remain the same. But a dear friend got married last month and all I could do was send him a message, and my niece is turning 18 next month and all I could do was record a video for her debut, which my whole family is flying to Cebu for. In between, I’ve agonized over what to write in the 3 inches of space afforded to me by postcards.

In my first month here, I set up a Telegram channel where I sent daily (!) updates to my friends about the banal things about my time here—random conversations with strangers, fruits I bought from the market, my first subway and bus ride. Small stories about the conveniences of living in a first world country, like libraries and affordable (?) pick-up, wash, and fold laundry services. In the months since, I’ve established a more-or-less reliable schedule for video calls, along with other methods of keeping in touch, like an email thread with

(with one email, in particular, that I reread to gain the courage to finally write this). In the year that’s passed, my friends have gone to my house to have lunch with my parents almost every quarter, which I think supplement the weekly video calls I have with them.My calls with my parents are often punctuated with “dog time,” or where my dad turns the phone around so I can say hi to my dogs. They don’t hear me when I call their names. But Gaby’s gone a bit more gray in the face since I’ve left, and Gizmo has become more rotund. They used to still try to sleep in my bedroom, but are now accustomed to sleeping in my parent’s room, where their beds have migrated. Each conversation with my parents begins with a tacit agreement: tell me what’s new, what’s changed, what have you been up to since—? And what are you doing this week? And next? I’ve asked my parents to watch TV shows with me, even though we rarely ever did that together back when I lived at home. I’ve had to get creative in creating new routines with them.

The summer has been strange. Even in the winter, I had nine hours of weak sunlight, I didn’t feel this type of lethargy. At first I thought the heat was what sapped my energy, but perhaps the truth is that in as much as the weather is akin to home, I know it isn’t. The sky looks different here, the humidity has a different heft. Anne Carson, when analyzing Sappho, said that ancient Greeks viewed the experience of love as one always in triangulation: it is bittersweet because it exists most purely in the reaching for the beloved. Much like the pothos, known for its vines: it’s easy to propagate because each leaf includes a node that creates new roots. It is in its nature to reach, to search for new soil, and once found, become bound and continue the cycle of reaching out once more.

I miss home. That ache encapsulates the bitter-sweetness of being here. What a blessing it is, to love so many people at home—to love them so much that it pains me, near constantly, to be away. And what a strange blessing too, to like being here. To manage my household of one. To be open enough to the world to make new connections, and go back to therapy to untangle old aches turned sharp in the face of a fresh beginning, and nurture my plants, and all this love. For months now I have feared admitting that I want to stay a bit longer, to let the tendrils of my desire unfurl beyond my room. What has informed that fear is something I have rarely acknowledged: that I am loved, that I am missed, that each person shaped emptiness in my heart is mirrored. In my conversations with my friends I have gleaned some truth—in as much as I selfishly wanted them to stay unchanged, the same is true of them, for me. To stay the same is easy. To want things to remain unchanged is natural. But there are still too many variables to account for. Nothing is constant. Not even me.

The Threatened One — Jorge Luis Borges Translated from the Spanish by Alastair Reid It is love. I will have to hide or flee. Its prison walls grow larger, as in a fearful dream. The alluring mask has changed, but as usual it is the only one. What use now are my talismans, my touchstones: the practice of literature, vague learning, an apprentice- ship to the language used by the flinty Northland to sing of its seas and its swords, the serenity of friendship, the galleries of the Library, ordinary things, habits, the young love of my mother, the soldierly shadow cast by my dead ancestors, the timeless night, the flavour of sleep and dream? Being with you or without you is how I measure my time. Now the water jug shatters above the spring, now the man rises to the sound of birds, now those who look through the windows are indistinguishable, but the darkness has not brought peace. It is love, I know it; the anxiety and relief at hearing your voice, the hope and the memory, the horror at living in succession. It is love with its own mythology, its minor and pointless magic. There is a street corner I do not dare to pass. Now the armies surround me, the rabble. (This room is unreal. She has not seen it.) A woman’s name has me in thrall. A woman’s being afflicts my whole body. El amenazado — Jorge Luis Borges Es el amor. Tendré que ocultarme o que huir. Crecen los muros de su cárcel, como en un sueño atroz. La hermosa máscara ha cambiado, pero como siempre es la única. ¿De qué me servirán mis talismanes: el ejercicio de las letras, la vaga erudición, el aprendizaje de las palabras que usó el áspero Norte para cantar sus mares y sus espadas, la serena amistad, las galerías de la biblioteca, las cosas comunes, los hábitos, el joven amor de mi madre, la sombra militar de mis muertos, la noche intemporal, el sabor del sueño? Estar contigo o no estar contigo es la medida de mi tiempo. Ya el cántaro se quiebra sobre la fuente, ya el hombre se levanta a la voz del ave, ya se han oscurecido los que miran por las ventanas, pero la sombra no ha traído la paz. Es, ya lo sé, el amor: la ansiedad y el alivio de oír tu voz, la espera y la memoria, el horror de vivir en lo sucesivo. Es el amor con sus mitologías, con sus pequeñas magias inútiles. Hay una esquina por la que no me atrevo a pasar. Ya los ejércitos me cercan, las hordas. (Esta habitación es irreal; ella no la ha visto.) El nombre de una mujer me delata. Me duele una mujer en todo el cuerpo.