The Terror of Getting Everything You Want

Or how I came to realize that what I was feeling, after all this time, has been grief

I was never any good at school. This apparently comes as a surprise to many of my friends, which in turn only reminds me that I'm not as transparent as I like to think I am. Whenever I told anyone this—that throughout my life my grades have been a C-B minus on average—people always say: But you're so smart. Well, yes I am. But whatever intellect I have doesn’t translate to good grades; the only time I ever did do well was in my last semester of college, when I had 15 units and barely any extracurriculars (aka, the school newspaper) to keep me busy.

Which is all to say: I’m no good at school, so it was difficult to reconcile why I wanted to go grad school so badly. Moreover, was this the reason why I was sad about getting into school, after everything?

In the last month I spent in Manila, every journal entry I wrote for a month featured some acceptance that what I was feeling was grief. I set out writing this essay trying to arrange the application process for grad school along with the well-known five stages of grief, but the framework didn’t fit: none of it was passive. I was going through tasks at each turn. William Worden, a critic of the five stages of grief model, provided an alternative, particular to those receiving grief counseling. In this alternative, Worden provides four tasks to engage those experiencing grief.

Task 1: To Accept the Reality of the Loss

Task 2: To Process the Pain of Grief

Task 3: To Adjust to a World Without the Deceased

Task 4: To Find an Enduring Connection With the Deceased in the Midst of Embarking on a New Life

I didn’t actually see a therapist for grief counseling: at the time, I don’t think I realized I was grieving at all, and even after all these years of therapy it’s still a struggle to be honest. My first therapist did say that the difficulty with me is that I’ve gotten too good at telling stories about myself, of convicing myself of the truth that pains me less. I took me a whole month to puzzle out how to write this all down, to explain why I did what I did and how I ended up here. It felt important to set it down, if only to remind myself, or to remember.

I. Accepting reality

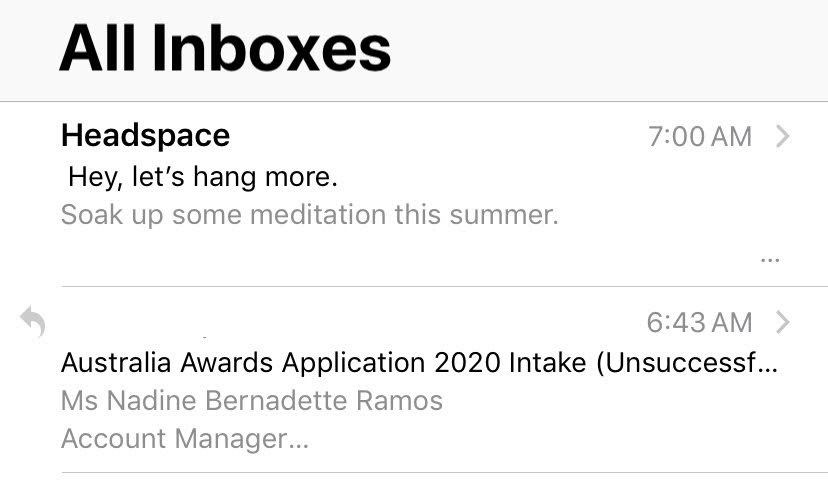

I first saw grad school as an easy way out (such as it is): a scholarship meant that I got to live somewhere else for two years and not have to worry about living expenses. In this train of thought, formal education was simply a side benefit—what was primary was the opportunity to leave. I tried first in 2019 for the Australia Awards and failed.

That desire to escape only festered throughout the pandemic, so much so that even during the 2022 Presidential Campaign, I knew that whatever the outcome, I was going to apply for grad school.

By July last year I'd made up my mind: I was going to try harder than I ever have for grad school, and it wasn’t just to run away. At that point I felt that I'd already grieved the loss of the elections—I felt, more than anything, driven to try something new. I'd tried my hand at public service, spent three years working in creative agencies, and even went full corporate. Nothing seemed to stick, and it wasn't for lack of trying.

I do well at work because I work hard: it's difficult for me not to. In 2021, I tried my hand at reconciling my relationship with work, but as I started work in 2022, I had to come to terms with the fact that the work that I do does matter to me deeply—and that, in itself, is not a terrible thing. It wasn't just that I was good at it. It's just that working in politics again, after half a decade, felt like rousing from a waking dream.

I hated that it felt like that; but oftentimes, anger is a mask for fear, and that was the truth of it. It terrifies me that it’s campaign work that lights up parts of my brain that no other job has. It terrifies me because working in politics subsumes me, and at the time, I didn't think that's what I wanted. After all, who would want a life without weekends or holidays, where knowledge was currency, where your brain was firing on all pistons constantly?

I wouldn't recommend this type of work to anyone; in fact, I'd already dissuaded some friends from following in my footsteps. It takes a certain type of person to choose this lifestyle, one that constantly tests your mettle, beyond the sheen of excitement involved in something most people can’t access. More often than not it's unglamorous, exacting, and a lot more life-threatening than I give it credit for.

I still wish deeply that I didn't like it. Even after the years I spent trying to build a life outside of it, returning to that life always hovered in my conciousness: a reminder of what I was capable of. I tried to build a life where I could plan ahead—could say with confidence that I could go on trips with friends and family, one not at constant threat of a crisis. I wished that I could be content with a normal job. Any job, other than campaigning.

But sometimes dislike wins over desire. After almost a decade working, I had multiple options, but I didn’t want to take any of the worn paths of previous industries. As much as I didn’t want to like politics and all its trappings, an avenue previously unpursued was the path of least resistance. I suppose that there's never a best time to stop running away from yourself—but the thought of turning 30 and still refusing to confront my desires, despicable as they seemed to me, felt more like a failure than anything.

II. Processing pain

For as much research as I did about applying to grad school, I wasn't prepared to face the enormity of my options. Rather than apply for a government-funded scholarship, which came with the trappings of a return-to-home clause or project execution, I decided to apply directly to schools which also provided scholarships. This was a double-edged sword, I'd soon find: while the Australia Awards or Chevening would provide a scope and limits to my applications, and essentially make the entire process of uprooting simpler, applying directly to universities and institutions felt like a shot in the dark.

Clarity came in the form of Y’s simple answer to filtering options for schools: “I would never study somewhere I didn't want to live.” I was already doing something similar: hours spent Googling schools in certain countries, then cross-referencing them to their Times Higher Education ranking, then finally, reviewing their curriculum and alumni. More than once I worked myself up into a frenzy, overloading myself with options, then exhausting myself when faced with paring it down to something manageable. After all, I couldn’t fathom writing more than three iterations of an application essay, nor could I stomach paying thousands of Pesos on application fees.

The filter of where to live had me zeroing on two countries in particular: Japan and Spain, countries I’d already been to and spent a significant amount of time in. Japan was also reasonably close enough to the Philippines that it would make visits easier, in either direction. As for Spain, it would be a direct path to getting Spanish citizenship—since Filipinos only need two years of legal residency to obtain it. I also speak some Spanish (a lot less than I used to) because of my minor in Hispanic Studies from over a decade ago.

I was firmly against studying in the United States. Other than the rise in Anti-Asian Hate crimes, nothing about the US appealed to me—likely another relic of my strong anti-imperialist days in college, but really. I knew that wherever I ended up, I’d be faced with microaggressions about my command of the language, and would have to prove myself regardless. I just didn’t care to do it in America.

This was, of course, antithetical to what I wanted to study: policy. Rather than pursue formal education in communications—a return to what I’d actually studied for my undergrad (Political Science) made more sense to me. Maybe the malaise brought about by my career options isn’t just rooted in the industries available to me, but to the work itself. And even if it wasn’t, it would benefit me more to give my experience a different dimension. Every few months in 2022 felt like I was untangling another thread in my relationship with the work that I chose to do, or the work that I was good at doing. The truth is, what excited me more than anything was to be bad at something again—to not know anything at all. The idea continues to excite me today, and that’s why I finally had the gumption to write this.

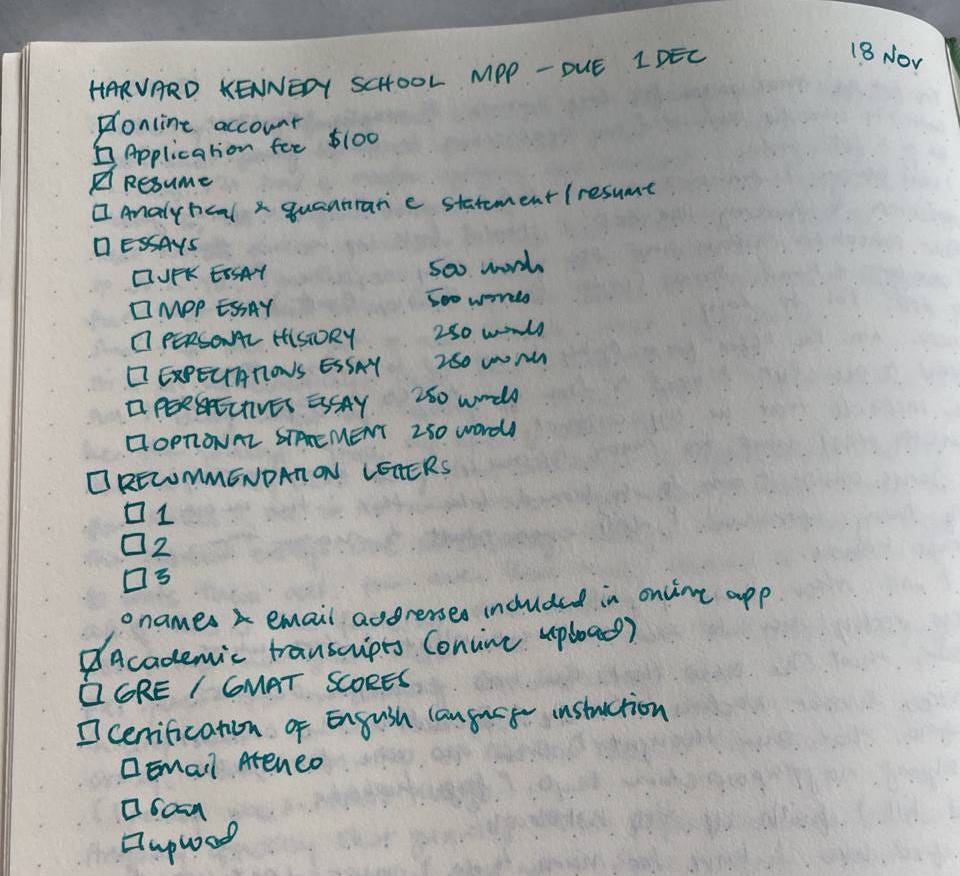

Preparing to apply for school was its own fraught journey, and it only got more intense when I approached a former boss and mentor to ask for a recommendation letter. I tried (and failed) to treat YO to lunch as thanks for taking the time out of her schedule to write a recommendation letter for me, and she was adamant that I apply for Harvard. I remember choking on my coffee. Harvard? Harvard???

It was J who told me that it would be good to have a "shoot your shot" school, an ideal school, and a back-up for my applications. Then swooped in R, who basically peer-pressured me into applying for Fordham. Thus any dreams of living in Spain fell to the wayside, and my options were narrowed down to three institutions: Harvard Kennedy School, Japan's National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, and Fordham University. Truth be told, I felt that I had the best chance of getting into the school in Japan—it was less known compared to the two in America, which hopefully meant I had less competition. I still shunned the idea of either school in America, but I supposed, at the time, that it didn't hurt to try. And more importantly, it was a lesson in quashing my pride.

II. 1. Processing pain (again)

The most difficult application is always the first. I blame the culture of shame so impressed upon Filipinos for my difficulty in filling out my grad school applications. There are no shortcuts to it, no easy way out—each application was an exercise in self-confidence. At first I tried to downplay my achievements because it's embarrassing to have to write it all out and sound like a self-important, arrogant asshole (much like writing this essay felt like). And as much as I wanted to present myself as someone worthy of millions of Pesos to fund my education, it was difficult to put those words to paper. It felt like I was either puffing out my chest or groveling.

I spent weeks researching tips for application essays, then more weeks just writing outlines and drafts. Applying for school took up all my waking hours—literally I would wake up, and my morning journal pages would be filled with thoughts on essay answers. Writing is always a solitary activity, and what made it worse is that somehow, I'd become so insecure of what I'd done, so I couldn't bring myself to talk to people about it.

Thankfully, I had friends who were willing to slap some sense into me: V, who reviewed my CV and the first draft of my notes for recommendation letters. R, my grad school guru and Fordham advocate, who reviewed my application essays and provided resources for the draft of my first research proposal in a decade. J and P, who were on their own grad school application journeys and kept me on track to my deadlines.

I'd decided against applying for schools that required standardized test results, simply because I didn't want to spend the money on it. Most people also begin reviewing for the GREs three months ahead of their exams, and I didn't think that I had the time nor the patience to go through it. But Harvard and Fordham required GRE results, so I crammed my reviews a month ahead of my exam. Thankfully there were numerous resources on YouTube about the quantitative section (I'm terrible at math! I'm convinced I have some form of math anxiety, even if I really like data). Studying for the GRE resurfaced the feelings of inadequacy that were long buried: who was I to think that I could hack this? That I could beat out hundreds (if not thousands, in the case of Harvard) of intelligent people who probably aced everything all their lives?

I finished my application to the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies over a month before it was due. That gave me enough time to write seven (yes, SEVEN) essays for Harvard Kennedy School and to take my GRE. By the time Fordham's deadline loomed, I was exhausted and half of me considered not even sending it in—of all three institutions, Fordham was the one who almost didn't accept a certificate from Ateneo for English instruction (which would have exempted me from taking the TOEFL or IELTS), and at that point I felt ready to set myself on fire. I submitted my Fordham application exactly on the due date, and then got a round of beers and sushi with B to celebrate my victory over all my applications.

Then came what may have been one of the most stressful periods of my life:

III. Adjusting to a world without

The period from January 9 to March 10 feels like a blur. A stressful, surreal blur. At one point in February I was working three jobs—consulting part-time for two agencies, and writing profiles on the side.

All of the forums, Reddit threads, and blog posts talked about the shared mania brought about by waiting for results: nobody, in the world, is cool about it. Somehow that made me feel worse—it felt like I had the rest of the world to compete with, too.

In my frantic attempt to keep myself occupied, I developed psoriasis (somehow this didn't show up during a Presidential campaign in the midst of a pandemic???) and also got a root canal. My therapist pointed out, years ago, that I need to work on being aware of my body. Or else it will just give up on me. Well, ladies and gentlemen, she was right.

I found myself oscillating between the deep belief that I'd get accepted into a school (so much so that I even began a grad school packing list), and then swinging abruptly to morose acceptance that I'd never get in. Eventually I looked up other schools that would open up applications in April and May, just in case. I am nothing if not a planner, and I planned for my eventual heartbreak: I had a 14-day trip to Japan with my parents in April, and I told myself that if I didn't get in a school, at least I had that.

At one point I tried to convince myself that I didn't actually want to go back to school, that I'd be fine without a masters degree—I had opportunities in Manila, and I was fine with that! (Of course I wasn't.) But for three months I liked to pretend. On top of that I reminded myself, almost daily, that I was happy in Manila and with my lot in life. Truly, I had no reason to complain—and I told myself that even if I didn't get in then at least I'd tried. And I had other options. I was beyond lucky to have so many in the first place.

IV. Enduring, accepting (?)

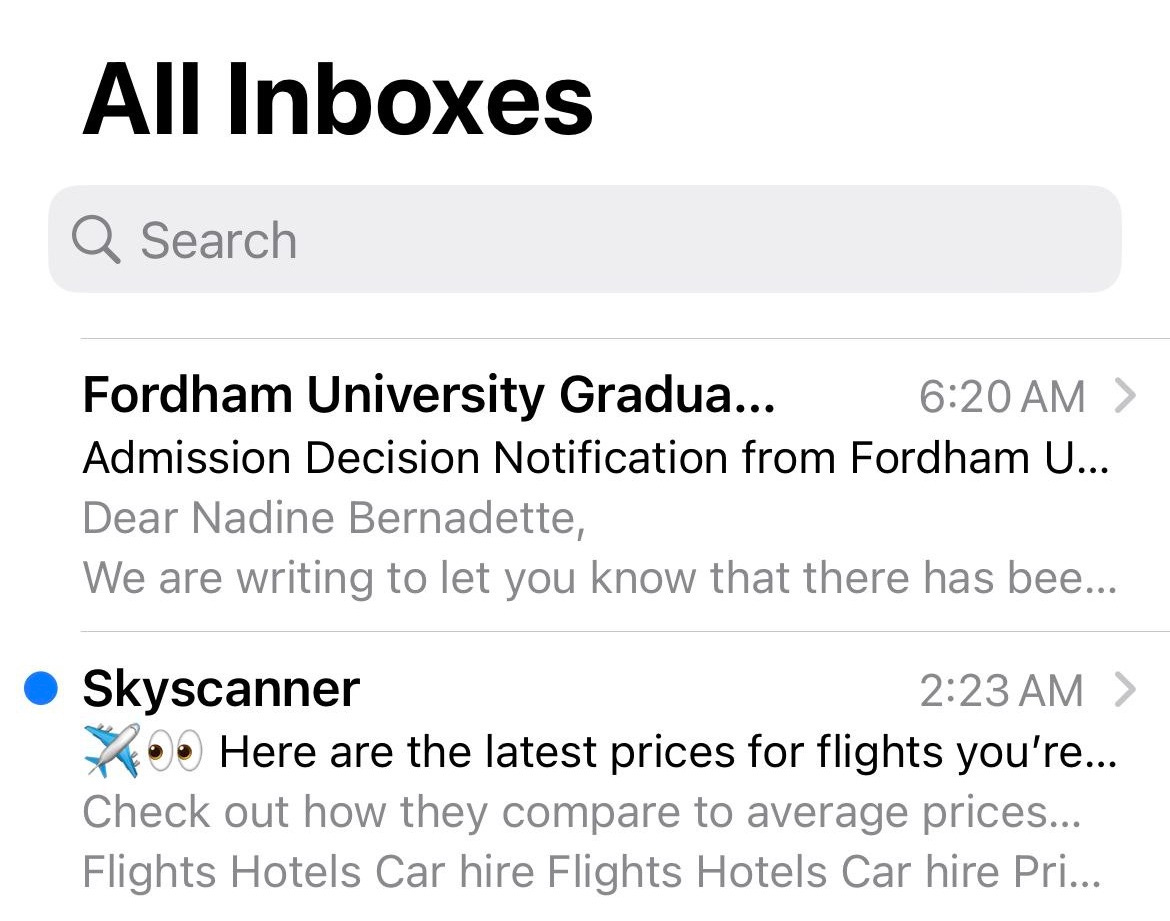

I woke up at 7AM on Saturday, March 10, to an email from Fordham. My hands were shaking as I held my phone, and I took a few minutes to brush my teeth and give myself a pep talk: Not the end of the world, you're not going to die, there are two more schools, and even after that there are more to apply to…

I sat outside on our porch and startled my dogs because of how loudly I was crying. The first words I read were congratulations, to go along with confetti animation on the website. I wish I could bottle that feeling: flooded with relief, and elation at a job well done. My heart felt like it was going to burst out of my chest. I'd never gotten a scholarship before, and this one came with a stipend, too—which meant I could actually afford to live in New York and go to school there. Me.

I spent those first few hours of the morning crying. I was still so full of gratitude and disbelief. Even now, five months later, I still find myself unable to accept that this is really happening for me; I don't know why I never thought I would. It's just—I've never been good at school. And now a program that accepts 12-15% of its applicants was essentially paying me to study.

Funnily enough, the joy didn't last long. Soon I found myself worrying about paperwork—first my visa, then an apartment—and I didn't feel good about any of it. I just felt stressed.

My friends tried to remind me to bask in the achievement but I couldn't. When previously I looked around my room with a sense of excitement at packing it all up, when the reality of my departure set in, I could barely bring myself to think of what clothes to leave behind. Rather than happiness, I expressed disbelief continuously. A word I used often was "surreal," because that's what it felt like: an alternate universe, one truly beyond my imaginings.

This brings us to the crux of it all: after wanting so badly to get into grad school—the desire strong enough to make me pray a novena, and write out little notes to God and the universe after each set of morning pages, begging them to give me this one thing—I wasn’t happy at all. In fact, I may have felt worse—an amalgam of unhappy emotions ranging from anxiety to sadness.

IV. Enduring, accepting (for real, this time)

There are only so many times a therapist can tell you, after a session, that you don’t need to come back. In a strange way it makes me feel worse (which probably means I should just find another therapist). It’s like they’re saying that I know how to handle it, so I don’t need to fork over so much money to be told so.

After so many months of wrangling with these bad feelings—and for a while, even up to a few weeks ago, I could barely give them a name—I decided to try a new therapist and talk to her about how terrible I was feeling about getting into grad school. It didn’t make sense: I got everything I wanted, down to the stipend and the program. I was faced with even more opportunities, and I got the rare opportunity to leave for free.

I told my therapist all of this, and she tried to get to the root of the anxiety. Was I afraid of failing? Afraid of school? No, I said firmly, not at all. I wasn’t worried about getting to New York and striking out on my own. It shocked me, the strength of my conviction in saying: It’s not about being bad at school at all. I think that learning new things is the one glimmer of happiness throughout the entire ordeal. But I still couldn’t find it in myself to be excited about going.

Then, she said: Well, you don't have to be excited.

No one had ever told me that. How could they? New York! Grad School! A full scholarship! Pursuing my dreams! How could I be anything other than excited?

Eventually, she said: I don't think you thought of what you'd be giving up.

And I hadn't. Not really.

Sure it was easy to think about all the fun, new, exciting things I'd see and do in New York. It was interesting to have to apartment hunt online, and look up what discounts I'd get as a student. But I didn't think of what it would take to actually get there—of what it would take to leave. Of what I'd be leaving behind.

After all, I wanted to go to grad school to challenge myself: I'd gotten too comfortable, but the comfort began to wear, like an old shirt that's overstayed its time in rotation. Then again, I've always kept those shirts anyway, even if only to make them into rags. As much as I thought I was ready for something new, the idea of letting go of that comfort filled me with grief. Not fear, but rather the great sadness that comes with letting go.

Leaving Manila, leaving home, meant letting go of all of it—and it meant grieving the life I wanted for myself but never got.

I was grieving over things beyond my control—conditions for a life I'd never have. A universe in which I worked for a winning presidential campaign, or one where I was content to work in the private sector with a stable job. I was grieving over the time I would never get back with my parents. I was grieving over the friends I'd likely not see for a year and a half, and who we would have been if we'd had that time to grow together, and celebrate together, and mourn together.

I grieved over not being there for the people in my life. I grieved over the idea that, even if we have Telegram and Zoom and Messenger, we would be hours and hours away for an unfathomable period of time.

I grieved over who I could have been. Or who I wished I could be.

How sick is it that after getting everything I wanted, I wished I was content? That the idea of all the opportunity laid at my feet, after months and years of working towards achievement, I still wish I could be happy with what I already had?

It's terrible to have to reckon with the magnitude of your own ambition. To have your soul brought to heel by the strength of your desire for more. I want it all—and it feels so soul-crushing to get what I want because I always forget to think of what it takes to get it.

I've been in New York for exactly a month now. That deserves its own telling. But as I've met with my cohort, I've had to tell them about myself and what I want: Hi I'm Nadine from the Philippines. One fun fact about me is that this is my first time in the United States. Before Fordham, I worked in a Presidential campaign, and I hope I can get a job here for a few years—but who knows, right?

I certainly don't.

Back in Manila, the thought was terrifying: I am nothing if not a planner, but so much of this next step in my life is out of my control. Certainly I'll try, and I'm sure that in some aspect I will succeed, but the goal has no name yet—or at least, not one I'm willing to speak. But these days to admit that feels freeing. In the spirit of this insane country, it feels okay to take the steps as they come, to chart a path forward with only a vague idea of where it ends. It tames the monster of my aspiration, gives me space to breathe. After all, I'm no good at school, but I'm pretty confident that I'm good at learning. For now, that's more than enough. Already, I spent a month learning about myself, removed from the comforts of home. That is achievement enough.

The Opposite of Nostalgia — Eric Gamalinda

You are running away from everyone

who loves you,

from your family,

from old lovers, from friends.

They run after you with accumulations

of a former life, copper earrings,

plates of noodles, banners

of many lost revolutions.

You love to say the trees are naked now

because it never happens

in your country. This is a mystery

from which you will never

recover. And yes, the trees are naked now,

everything that still breathes in them

lies silent and stark

and waiting. You love October most

of all, how there is no word

for so much splendor.

This, too, is a source

of consolation. Between you and memory

everything is water. Names of the dead,

or saints, or history.

There is a realm in which

—no, forget it,

it’s still too early to make anyone understand.

A man drives a stake

through his own heart

and afterwards the opposite of nostalgia

begins to make sense: he stops raking the leaves

and the leaves take over

and again he has learned

to let go.